Last week, the Happy Planet Index 2024 report made its debut, published by the HotorCool Institute. My acquaintance with the HPI index dates back to my master’s research in 2017, delving into welfare measures. The HPI calculates life expectancy multiplied by self-reported well-being and then divides the result by consumption-based carbon footprint. I recall that in 2018, the equation involved the ecological footprint instead.

This year's report, drawing data up to 2021, seeks to spotlight countries achieving individual well-being and longevity while maintaining a low carbon footprint. According to the latest UNEP emission report, the safe threshold for carbon emissions stands at 3.17 tons per person. Self-reported well-being data stems from the World Happiness Report Gallup-backed data, scored from 1 to 10, while life expectancy data is sourced from the United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2022).

Life expectancy

Self-reported wellbeing

Carbon footprint

The overall HPI

Surprisingly, the top scorer this year is Vanuatu, an idyllic island nation in the South Pacific. With a life expectancy of 70.4 years and a self-reported well-being score of 7.1 out of 10, Vanuatu has a carbon footprint well below the globally fair share of 3.17 tonnes CO2e per capita.

Sweden claims second place, boasting significantly higher life expectancy and self-reported well-being compared to the affluent nation of Sweden (83.0 years and 7.4 out of 10, respectively). However, Sweden's per capita carbon footprint is more than three times larger. Nonetheless, it still maintains a lower carbon footprint compared to most similarly wealthy countries, standing at 8.7 t CO2e per capita in 2021 – a figure 16% less than Germany's and less than half of the USA's per capita footprint.

Costa Rica, a perennial leader in the HPI since 2009, has slipped to fourth place, partially due to the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, it's remarkable that despite a carbon footprint slightly above the fair consumption level at 4.4 tonnes CO2e per capita, Costa Rica continues to achieve some of the highest levels of well-being globally.

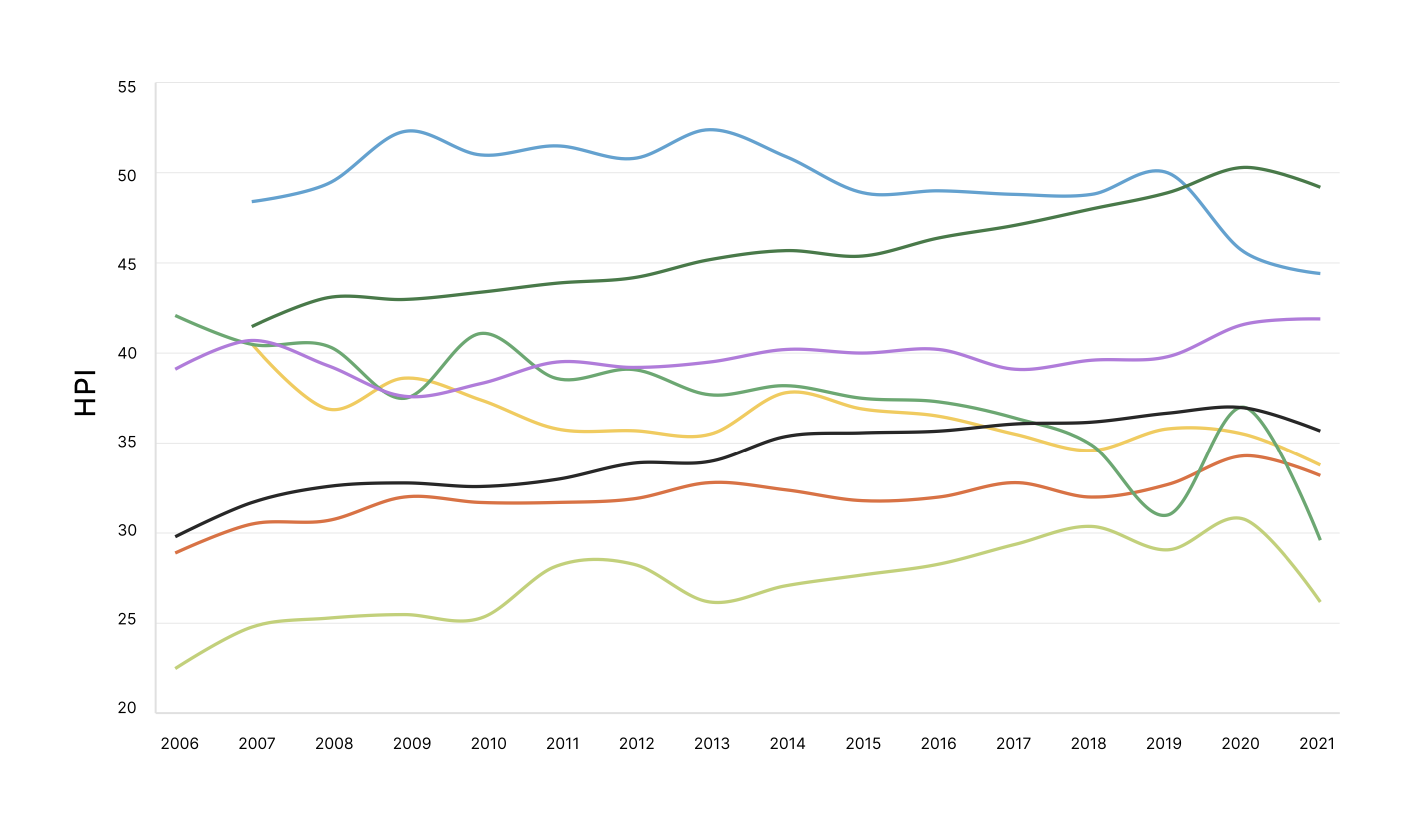

Regions development

The report underscores a common focus on citizen well-being and public investment among these top-performing countries, although as a Swede, I've observed a contrary trend in recent years. The crux is that high carbon emissions and robust GDP growth are not prerequisites for well-being and longevity. Among the top ten countries with the highest per capita GDP, six have below-average HPI scores, suggesting that prioritising GDP alone does not necessarily lead to enhanced well-being within environmental limits.

For the first time, this report delves into inequalities within HPI scores within countries, revealing stark differences. In the USA, for instance, the top 10% of earners exhibit an average carbon footprint of 68.7 tonnes CO2e per capita, compared to 23.6 tonnes for the eighth income decile. The corresponding benefit in well-being is marginal, indicating that high-income earners with significant carbon footprints experience little improvement in self-reported well-being. Interestingly, excluding top-income earners would significantly boost HPI in Mexico due to their disproportionately high carbon emissions.

HPI doesn't aim to supplant GDP but rather emphasises the need for alternative measures and indicators that truly capture what matters. It's a call for prioritising happy life years as a proxy for society's ultimate goal, echoing a demand for such indicators from organisations like the IUCN (World Conservation Union).

Furthermore, HPI in relation to GDP reveals that GDP alone doesn't contribute significantly to HPI. While there's a modest increase in average HPI with GDP up to a certain threshold, the relationship weakens thereafter, explaining only 21% of the variation in HPI. Notably, this relationship is strongest for low-income countries, suggesting that GDP may contribute to well-being and life expectancy in such contexts without significantly increasing carbon emissions.

References to different indicators in the media

Reflecting on trends over time, the pandemic has undeniably impacted HPI, albeit differently across regions. West Europe, for instance, witnessed a rise in life expectancy alongside a reduction in carbon emissions, albeit insufficient to meet the Paris Agreement targets. Conversely, in East Europe, emissions remained stagnant while well-being and life expectancy increased.

Finally, the report underscores the role of climate action in addressing inequality, highlighting that the top 10% of income earners globally contribute roughly half of all emissions. In Europe, this group's carbon footprint surpasses that of the bottom 50% of the population, emphasising the imperative of tackling inequality to combat climate change effectively.

In essence, it's time to redirect our focus towards what truly matters and measure our progress accordingly. By addressing major challenges and prioritising well-being and planetary prosperity, we can pave the way for a more sustainable and equitable future.

Read the report here!